To start my Women in Science series, I’ll present information on a scientist with whom I share a birthday – Dr. Maud L. Menten, Biochemist from Canada. Born in Port Lambton, Ontario in 1879, Dr. Menten graduated from the University of Toronto in 1913 (some sources say 1911).  Later in 1913, she was an author for the article “Die Kinetik der Invertinwirkung” which introduced the Michaelis-Menten equation, used to relate the reaction rate of an enzyme to the concentration of a substrate.

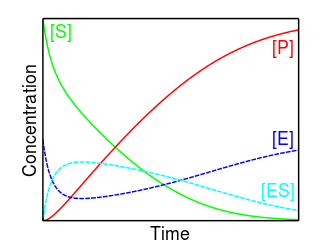

Later in 1913, she was an author for the article “Die Kinetik der Invertinwirkung” which introduced the Michaelis-Menten equation, used to relate the reaction rate of an enzyme to the concentration of a substrate.

The reaction rate increases with increasing substrate concentration ![[S]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/math/3/8/b/38bd6c19740e43396bd14b1575d58f60.png) , asymptotically approaching its maximum rate

, asymptotically approaching its maximum rate  , attained when all enzyme is bound to substrate. It also follows that

, attained when all enzyme is bound to substrate. It also follows that ![V_\max = k_\mathrm{cat} [E]_0](https://upload.wikimedia.org/math/c/4/b/c4bde41958e29d794fda5e9cdf3a949d.png) , where

, where ![[E]_0](https://upload.wikimedia.org/math/3/5/7/357bc494f724ede952492cec26d55c2a.png) is the initial enzyme concentration.

is the initial enzyme concentration.  , the turnover number, is the maximum number of substrate molecules converted to product per enzyme molecule per second.

, the turnover number, is the maximum number of substrate molecules converted to product per enzyme molecule per second.

Her contributions to science continued long after the Michaelis-Menten equation. She made additional discoveries/co-discoveries relating to hemoglobin, blood sugar, and kidney functions. Because women were not generally able to work in the medical field in Canada at the time, she ended up working mainly in the US with some time spent in Europe, as well.

Dr. Menten continues to be honored today by the Dr. Maud L. Menten Memorial Lecture Series.

The Dr. Maud L. Menten Memorial Lecture Series is held annually by the Department of Biochemistry. Two mini-symposia and at least eight lectures will be held each year. The speakers are expected to be active, high-profile scientists and are nominated by the Department of Biochemistry research community. Invitations are sent after selection of the speakers by the Dr. Maud L. Menten Memorial Lecture Series Committee.

Just sharing this New York Times article that goes into some depth on a look at this question. When you start with this:

Just sharing this New York Times article that goes into some depth on a look at this question. When you start with this: